It’s no secret that our industry is experiencing a very challenging market right now. We are seeing layoff announcements practically every day, and while we are not quite ready to re-establish “Implodometer.com” (remember that!), there are already a handful of companies shutting down. M&A activity has exploded (my colleagues Garth Graham and David Hrobon are running at full speed) as the industry begins to consolidate. We are in a classic downcycle with too many lenders chasing too few loans. Operations executives are in survival mode, trying to maintain service levels while shedding staff.

Even in challenging times, lenders still need and want high-producing, purchased-focused Loan Officers (LOs). But how do lenders recruit these sales superstars?

The usual toolset includes building relationships, networking at industry events and selling the lender’s value proposition to prospective LOs. But compensation is always a key part of the value proposition, and for high producers, signing bonuses have been a big part of the story.

So, what is happening with signing bonuses? Where have we been and where are we going?

I recently interviewed six distributed retail sales executives to explore the concept and history of signing bonuses from their perspectives. This article will leverage some of those conversations as well as our experience working with our clients on sales compensation structures and strategies.

The signing bonus concept is straightforward and self-explanatory. It involves the payment of money to new loan officers both upfront and early in their tenure with the new lender based on them hitting certain targets (see more detailed discussion of structures below).

So why are signing bonuses common for distributed retail LOs? There are a couple of good reasons.

High Demand — There has always been a high demand for high-producing loan officers in the distributed retail channel. Good LOs have strong referral partner relationships and a deep set of relationships with prior customers in the communities in which they live. Even with the large and growing number of digital tools and data sources available to lenders, distributed retail is still very much a people and relationship business, especially in a purchase-dominated market.

Free Agent Mentality — In addition to being in high demand, high-producing LOs often have a “free agent” mentality. While retail LOs are employees of their company, they think of themselves as free agents and often are more focused on their personal brand. This means they are more likely to jump ship if another lender comes along with a better offer. Loan officer turnover data supports this, with average annual turnover typically in the 30-40% range and average tenure in the three- to four-year range. When one considers the high demand for quality LOs and their free agent mentality, it is easy to understand why signing bonuses have long been a part of the equation.

Independent mortgage bankers (IMBs), and especially large IMBs, are more likely to pay signing bonuses to retail loan officers. This does not mean that banks don’t pay signing bonuses at all. But they are far less likely to pay them, and if they do, it may be for special circumstances, such as targeting an affordable housing specialist.

Signing bonuses do not match up well with a typical bank’s culture. Banks have trouble accepting the free agent mentality of LOs. Quite frankly, they don’t want loan officers who aren’t inclined to “wear the bank jersey.” Imagine the discussion in the bank HR department when asked to approve a six-figure signing bonus. I can almost hear them say:

“How does this fit into the standard compensation structure for the sales side of the bank?”

“How can a mortgage salesperson potentially make more than the bank regional president?”

One bank sales executive I interviewed said, “The goal is quality growth at the right price. Culture is more important to us.”

In our experience, IMBs are more likely to ramp up and down aggressively as market conditions ebb and flow. They must — it’s a matter of survival. But banks don’t like to operate with an easy come, easy go, hire and fire mentality. It is well documented that banks have lost market share to IMBs and there are many reasons for this. The lack of willingness to pay top dollar for high producers is one of them.

While there have been many variations, there are some common structures that are used when paying signing bonuses. Let’s start with an illustrative example.

A lender expects a prospective LO to fund $80 million in annual volume. The lender may propose to pay a signing bonus of 50 basis points (bps) on that volume or $400,000. Then the question is the timing of payment. It has been common in the industry to pay a certain percentage of the bonus upfront upon signing and then pay the remainder based upon the achievement of production targets. In our example, the lender may pay 50% upfront ($200,000) and agree to pay an additional 25% ($100,000) when the LO reaches cumulative volume of $40 million and the final $100,000 when the cumulative target of $80 million is reached.

The amount of the signing bonus, timing of payment and the volume trigger structure are all negotiable and vary greatly depending on the historic production levels of the loan officer, market conditions and the lender’s view of Payback Period and Return on Investment (ROI) — more on that below.

It is common for lenders to establish “clawback” provisions in the LO employment agreement. If the LO leaves the lender within a certain timeframe, the clawback provision obligates the loan officer to repay the signing bonuses to a certain extent. For example, in the case of an LO who starts at the beginning of the year, if the LO leaves during:

Clawback periods have varied greatly, but it is not uncommon to have periods range from six to 24 months, depending on market conditions.

While clawback provisions are common, they can be difficult to enforce. Clawbacks mean the departed loan officer is on the hook; the question is whether legal action and the pursuit of a settlement is worth it. While many lenders understand the difficulty of enforcing clawbacks, most agree that it is still prudent to hold LOs’ “feet to the fire.” Also, the existence of the clawback may compel the new lender to consider a buyout of the remaining clawback amount. Even if the lender is unsuccessful in collecting clawback payments, there is some ability to recoup some of the amounts due by holding back final checks and trailing commission payments after the LO has left the company. Of course, lenders should consult with legal counsel to ensure compliance with employment agreements and applicable labor laws prior to withholding trailing commission amounts.

While clawbacks appear to be prudent from the lender’s point of view, it reinforces the transactional nature of the relationship. One sales executive I spoke with said he marks his calendar to notate when clawbacks expire for departed LOs. For example, if some top LOs have been recruited by a competitor with a 12-month clawback, he marks his calendar to reach out to them in month 11!

In the old days, lenders would rely on reviewing W-2 information and screenshots of production information from prospective LOs. For example, if an LO made $120,000 in the prior year, a lender may decide to guarantee $10,000 a month for the first few months or pay a signing bonus of say $30,000 to $50,000. Now there are third party data sources from companies such as Mobility Market Intelligence (MMI), CoreLogic, InGenius and Model Match that arm the lender with better data to assess the viability of prospective loan officers.

Since the LO’s license number is now attached to fundings, there is a wealth of data available to better understand important considerations, such as purchase versus refinance mix, product mix and production volume trends. In one of my recent discussions, one sales executive told me that a lender recently sent text messages to prospective LOs with actual dollar amounts of estimated bonuses that they would pay based on available public data. While ubiquitous data on loan originators may level the playing field, it also increases the already sky-high recruiting intensity for top producing LOs in both good markets and bad.

In a market with wide profit margins and high volume, signing bonuses are easy to justify. While signing bonuses were very high in 2020 and 2021, lenders could likely justify them based on payback period.

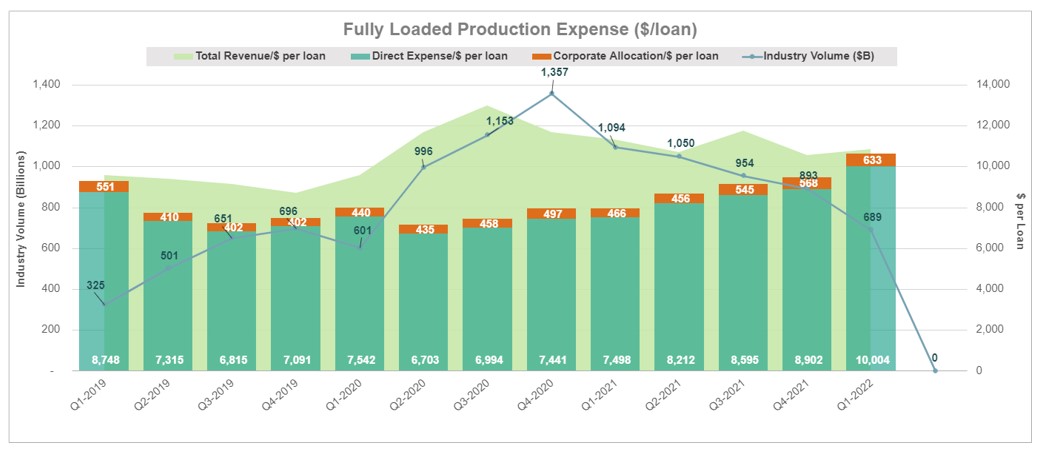

Chart 1

Source: MBA Quarterly Performance Report Q1 2022.

Source: MBA Quarterly Performance Report Q1 2022. The chart above summarizes data from the MBA’s Quarterly Performance Report. The light green shaded area represents revenue while the bar graphs reflect expense. The line graph shows the production volume trends. Obviously, the large gap between revenue and expense which started in 2019 and then exploded in 2020 and 2021 clearly shows what we all know to be true – industry profits reached record levels in 2020 and 2021 and were largely driven by extraordinarily high revenue. Lenders paid large signing bonuses in 2020 and 2021 and it likely made sense at that time.

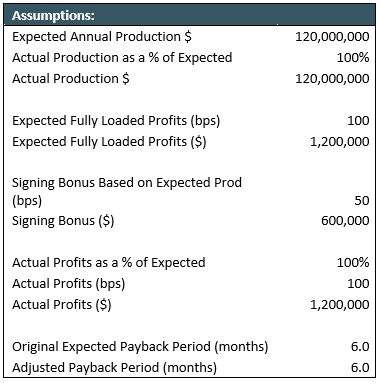

STRATMOR created the following analysis which demonstrates how changes to expected volumes and profit margins can dramatically impact payback periods. First, we start with the baseline assumptions:

Chart 2

Source: © 2022 STRATMOR Group.

Source: © 2022 STRATMOR Group. In this example, we are assuming that the prospective LO was expected to fund $120 million in volume over the next 12 months. Also, in the base case, we are assuming that the lender expects to make 100 bps profit from the retail channel on a fully loaded basis, which would assume profits of $1.2 million on that production. We are also assuming that a signing bonus of $600,000 was paid based on 50 bps times expected volume of $120 million. Given the baseline assumptions, the lender would be expected to recoup the $600,000 signing bonus in six months.

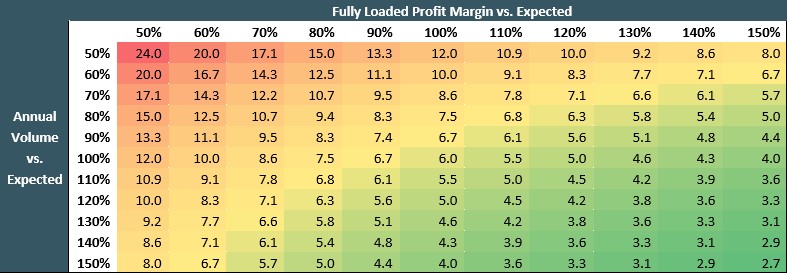

The table below calculates the impact of varying production levels and fully loaded profits on the payback period:

Chart 3

Source: © 2022 STRATMOR Group.

Source: © 2022 STRATMOR Group. That example is probably not far from what we are experiencing in today’s market. Volumes are down at least 50% for many lenders, and profits have deteriorated to the point where breakeven may be aspirational at this point. The math is straightforward — to achieve a six-month payback period based on fully loaded pretax net income, the signing bonus should be 50% of the profits. For example, if profits are expected to be in the 30-40 bps range, the signing bonus should be in the 15-20 bps range if a six-month payback is desired.

Of course, one could justify paying signing bonuses based on the Contribution Margin expected (Incremental Revenue less Expected Direct/Marginal Costs). That may work if the number of signing bonuses are limited, but it would be a bad business decision if the practice is widespread within a given company. Not all volume can be deemed marginal.

One final and important note: While it is interesting and useful to consider the payback period for signing bonuses, at the very moment you achieve the payback on your signing bonus investment, you have merely broken even on your investment. At that point, your Return on Investment (ROI) is zero!

Given the above example, it is reasonable to expect lenders to recoup their signing bonus investment in at least six to twelve months. In thinking about where retail channel profit margins have been over the past three years, the level of signing bonus payments is not surprising.

In 2018 and early 2019 when profit margins were in the 40-50 bps range, signing bonuses or guarantees in the 20-30 bps range would not have been out of the ordinary. In that timeframe, in addition to attracting top LOs, the goal was to ensure that the incoming loan officer had a guarantee or a floor on compensation to bridge the gap while they built up their pipeline at the new lender. Also, lenders did not and do not want to give the LO any incentive to inappropriately move a pipeline of locked loans to the new company.

In 2020 and early 2021, when retail margins were 150 to 200 bps, it was not uncommon to see signing bonuses in the range of 75 to 100 bps on volume, and some very large volumes at that. These “monster signing bonuses” as one lender recently put it, were paid out during this time frame but could be financially justified given the margin and production levels. In the context of the above analysis, one could still pencil out a six-month payback period given the margin environment.

Market conditions in 2022 do not appear to support the same level of signing bonuses seen in 2020 and 2021. One sales executive I interviewed believed that signing bonus amounts paid are down 50% from what he saw in 2020 and 2021, but they are still not down to 2018 levels. While the estimated reduction in signing bonuses is up for debate and may vary greatly by market and specific facts and circumstances, it is not hard to imagine that they are down materially given the drop in volumes and margins.

Mortgage lenders that want to grow volume are willing to make a financial investment to do so. This investment can occur at the LO level, the branch level or at a company level via an M&A transaction. While this article is focused on signing bonuses for individual loan officers, the same principles apply to the acquisition of a branch or an entire company. In each case, there are typically the same component pieces:

In each case, the buyer carefully evaluates payback period and ROI. Of course, M&A has additional risks and rewards. For more on this, here is a link to an article on the M&A market authored by STRATMOR Principal David Hrobon.

In our experience, many lenders are philosophically opposed to the notion of signing bonuses. While this may cause them to miss out on recruiting certain high producing loan officers, there are key reasons why they resist the temptation:

One lender I spoke with has tried to change their focus to recruiting “mid-tier” LOs and grow them to “mega producer” levels. The lender shared that, “Mega producers act like free agents. We want our producers to value the company culture, operations capability, and sales support. We want them to view the relationship as a partnership, not a free agency.”

Another lender summarized their viewpoint as follows: “I am wary of the transactional mentality of certain loan officers. You tend to get shopped after the transaction period ends.”

As the name implies, lenders are compelled to pay retention bonuses when they feel that an employee may be at risk of being hired by a competitor. On the sales side, this often arises when a high-producing loan officer receives an offer which includes a signing bonus. The retention structure may include a combination of bonus and an increase in basis points of commission for a finite period. In many cases, the LO does not want to leave his/her company but has received a sizable offer that is worthy of serious consideration. Since the LO often wants to avoid the risk of switching employers, there may not be a need to match the competing offer one for one.

Of course, not every competitive situation results in the payment of a retention bonus. The lender is at an advantage here because they have data on the LO which allows for an informed decision. Factors considered in payment of retention bonuses include the following:

As one might expect, we are hearing that retention bonuses are on the decline as the frequency and level of signing bonuses has fallen off.

Since high producing LOs will always be in demand and the “free agent mentality” of many LOs won’t disappear any time soon, signing bonuses will continue to be a part of the mortgage recruiting landscape for years to come. Signing bonuses can certainly be justified for certain LOs in certain markets. As discussed above, one can buy an LO, buy a branch, or buy an entire company. In each case, an upfront investment is required which can be fully justified, supportable and a prudent business decision. The key is for lenders to focus on expected volumes, do the math and stay disciplined. Importantly, the focus should always be on recruiting salespeople who fit your culture.

There are many lenders who are philosophically opposed to the concept of signing bonuses. They don’t want to get stuck in the ongoing market whipsaw, paying large bonuses when times are good and then quickly retrenching when conditions change. For these lenders, the focus is on making the LO feel tied to the company culture and less like a free agent. The goal is to establish a career path with sales professionals that pays well over the long haul, without falling into the short-sighted trap of paying signing bonuses and experiencing higher than average turnover as a result.

Our focus in this article has been to provide a balanced view of the issues germane to the payment of signing bonuses. There is no single “right” answer. Lenders must choose their path in the context of their overall strategy, vision, values and corporate culture.

At STRATMOR, we have a long history of working with our clients on the development of long-term strategies and a target operating model and on compensation strategies that enable and support the achievement of corporate objectives critical to long term success. If you need assistance with the development of your overall strategy and supportive compensation strategies, feel free to contact us for an exploratory discussion. Jim Cameron

STRATMOR works with bank-owned, independent and credit union mortgage lenders, and their industry vendors, on strategies to solve complex challenges, streamline operations, improve profitability and accelerate growth. To discuss your mortgage business needs, please Contact Us.